Authors:

Published:

When I think about data, caselaw isn’t the first thing that comes to mind.

The word “data” evokes tabulated click-through rates, aggregated housing statistics, and short, readily classifiable chunks of born-digital text. Multi-page 19th century legal documents don’t exactly fit the archetype.

Practically speaking, of course, all it takes for a body of material to become usable ‘data’ is a person or organization willing to make that material accessible to analysis. The HLS Library Innovation Lab’s Caselaw Access Project represents an effort to do just that for centuries of American caselaw. Through resources generated and maintained by the Caselaw Access Project, researchers can explore the rich legal history of the United States byte by byte.

If the rise of big data has taught us one thing, however, it is that “can” does not necessarily imply “should.” Indeed, the practice of subjecting core texts from the humanities and social sciences to data-driven analysis has been met with sharp resistance from some quarters. A widely discussed essay by Daniel Allington, Sarah Brouillette, and David Golumbia criticizing the “Digital Humanities” movement recently argued that the application of quantitative methods to such material has driven “the displacement of… humanities scholarship and activism in favor of the manufacture of digital tools and archives.” To the essay’s writers and others of similar mind, the expansion of data’s domain comes as a threat to the integrity of a long tradition of scholarship.

In this post, I present my experience working with the Caselaw Access Project’s publically available Illinois dataset as evidence for a more optimistic narrative – namely that applying quantitative techniques to corpuses primarily associated with the qualitative disciplines can help us to uncover and relate stories which might otherwise go unnoticed.

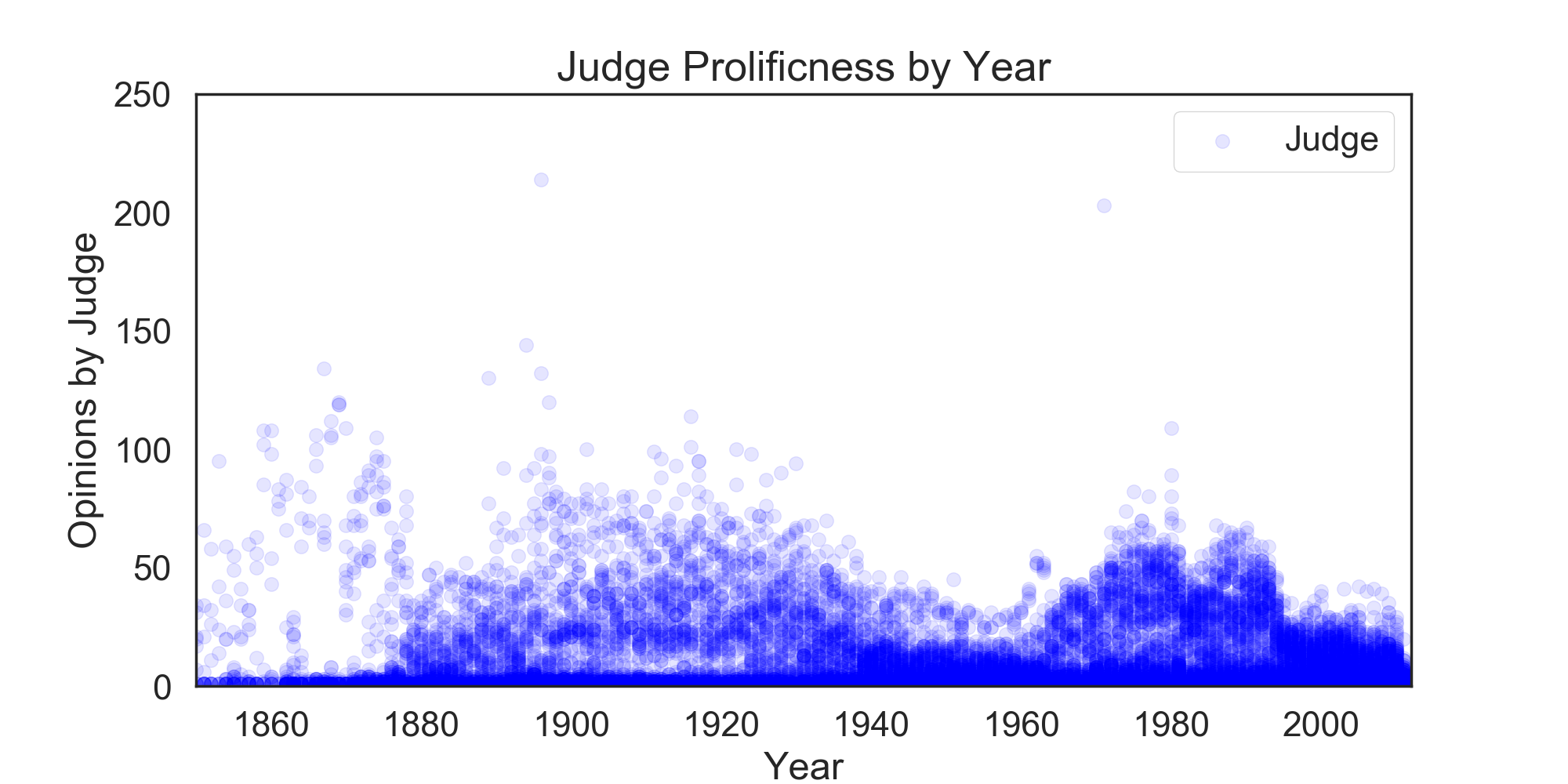

I uncovered this particular story while messing around with measures of “prolificness” amongst Illinois judges between 1850 and the present. I had generated a plot tracking the number of opinions judges had published per year over the timespan (each point corresponds to one judge’s output over the course of one year):

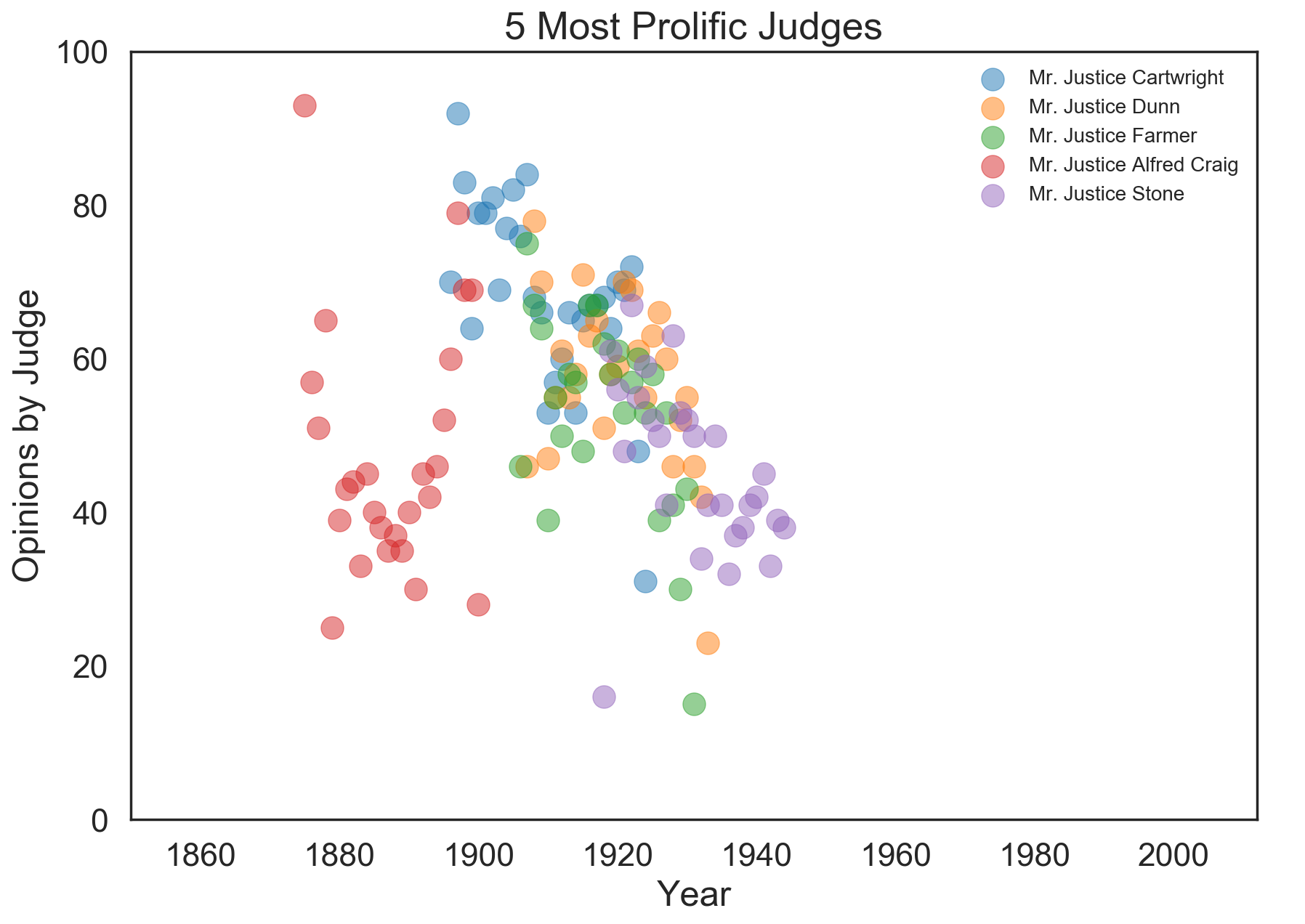

I noticed an interesting trend – in a window of time between about 1890 and 1930, many justices were publishing upwards of 50 opinions per year (it’s worth noting that modern publication numbers have likely been pushed down by the rise of unpublished opinions, which are not indexed in reporters and therefore cannot be cited as precedent). Digging down a little further, I plotted yearly publication volume for the 5 Illinois judges who wrote the most opinions over the course of their careers.

All of these judges fall more or less into the timespan discussed, and all were justices of the Illinois Supreme Court. Running the numbers, it became apparent that one Mr. Justice Cartwright was firmly in the lead as the most prolific publisher of legal opinions in the history of the state of Illinois.

My efforts to investigate Cartwright’s life and times through internet research were largely unfruitful. Among the most complete sources I found was a short profile on a website dedicated to social reformer Florence Kelley, which cites just two brief articles about Cartwright – both of them published in the 1920s. A brief Wikipedia entry provides a portrait of the justice taken in 1919, about five years before his death.

From these paltry sources, I learned that Cartwright was born in Iowa Territory on December 1st, 1842. After serving with some distinction in the Civil War, he attended Michigan Law School starting in 1865. Between 1868 and 1876, he served as general attorney for a regional railroad company. After a period of private practice, Cartwright was elected as a circuit court judge in Oregon, Illinois in 1888. In 1895, he became a justice of the Illinois Supreme Court – a position which he held until his death on May 18th, 1924.

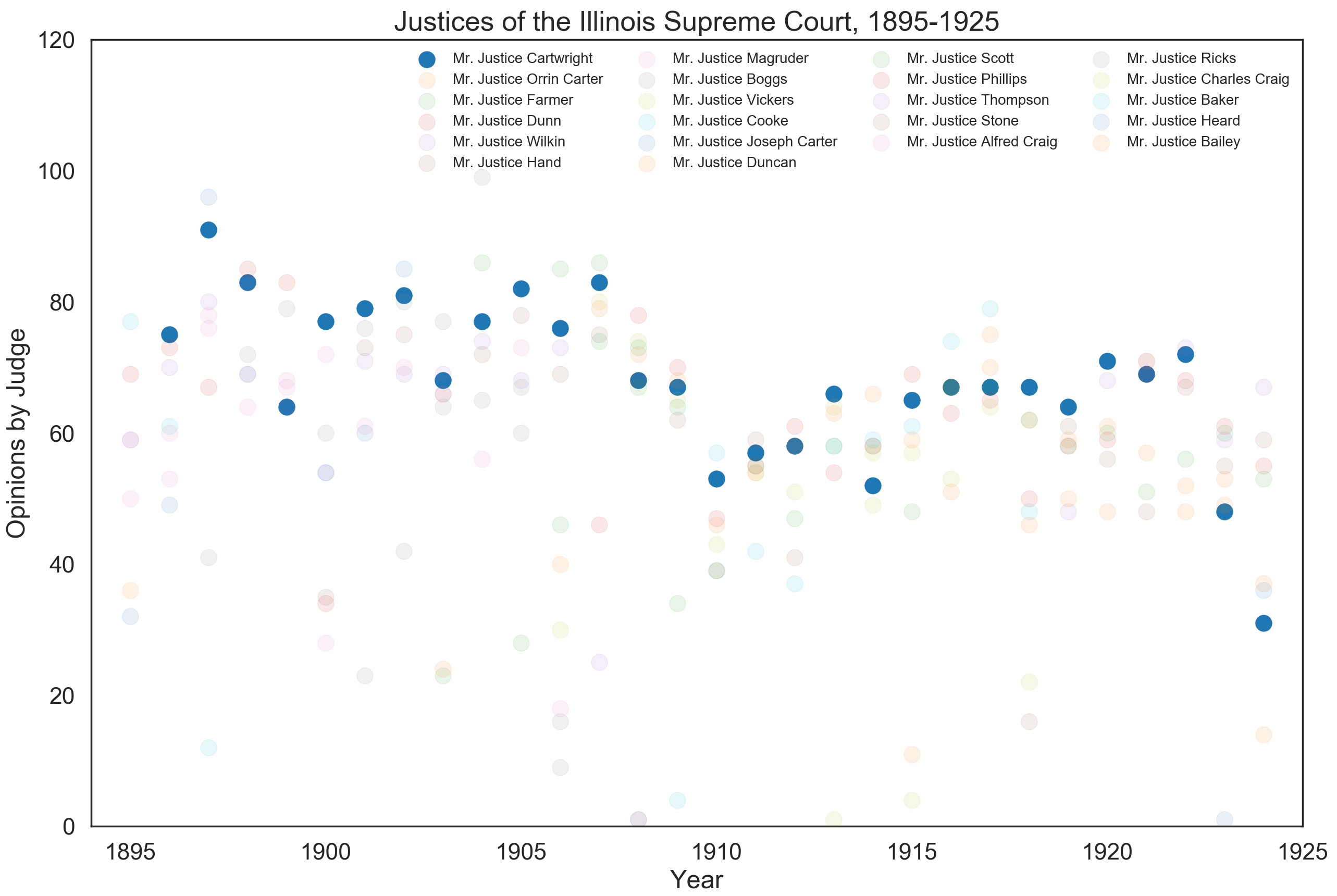

However, none of the sources I was able to locate shed much light on Cartwright’s amazing prolificness, though some of the articles written around the time of his death do reference it offhand. For further insights, I turned to the data. After cleaning and standardizing data corresponding to Cartwright and his peers on the Illinois Supreme Court across his almost 30-year career, I visualized the yearly output of of each justice present in the dataset.

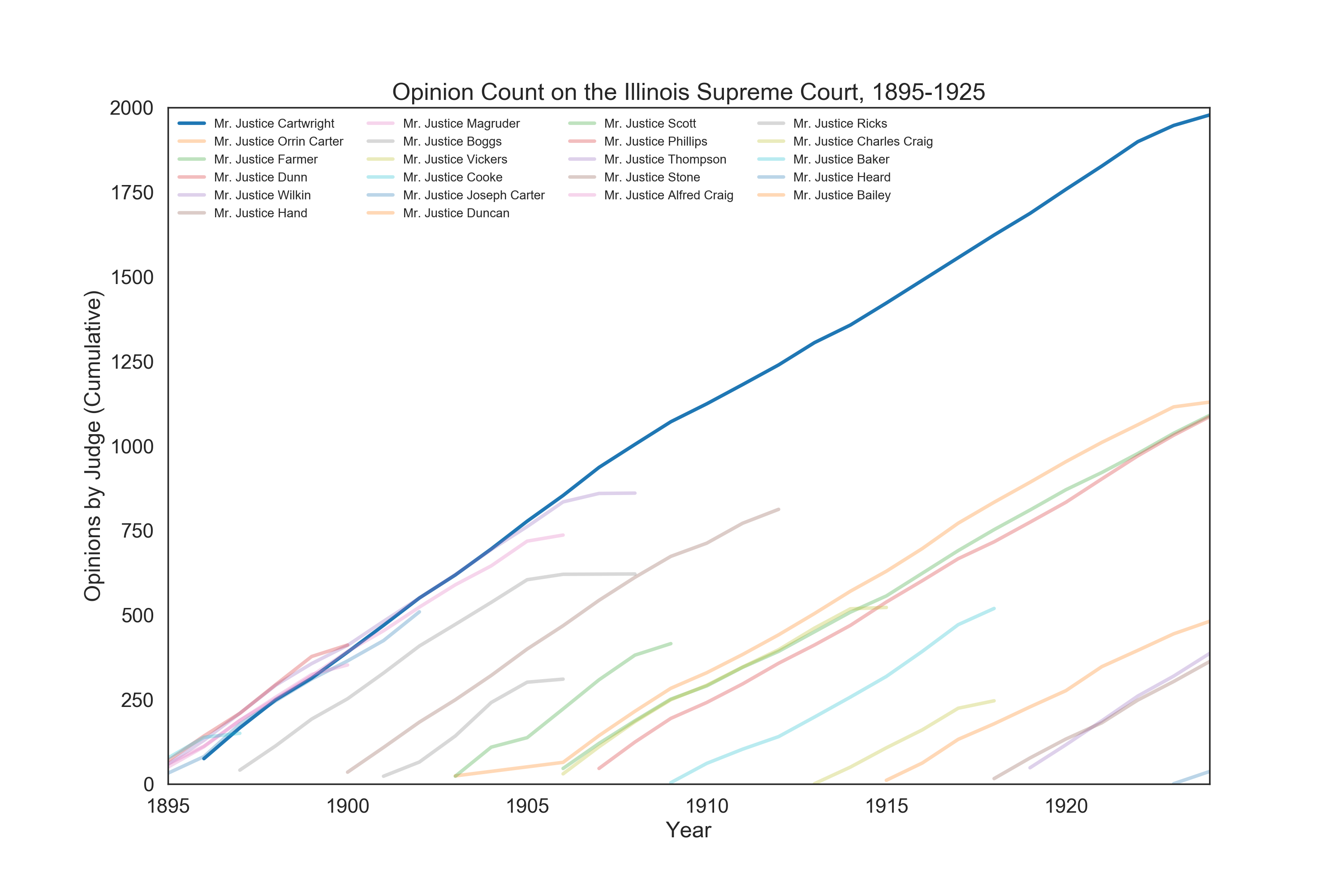

With a few exceptions, Cartwright was among the most prolific publishers on the court throughout his time as a justice. He was particularly active in his early years of service, with a marked drop off in the two years immediately preceding his death. However, it is clear from the visualization above that Cartwright wasn’t writing enormously more than his peers – there is often at least one justice who authors more than him in a given year, and he occasionally winds up in the middle of the pack. Where, then, does his dominance come from? To find out, I generated a cumulative plot of the number of opinions written by each justice in the span between 1895 and 1925.

As we can see, it is not just Cartwright’s yearly rate of production that catapulted him to dominance – it is also his consistency. In the years between 1896 and 1922, just once did Cartwright have an annual output of fewer than 50 opinions. Over the course of a lengthy career, he kept up this breakneck pace with a degree of longevity and persistence that seems to have eluded his peers.

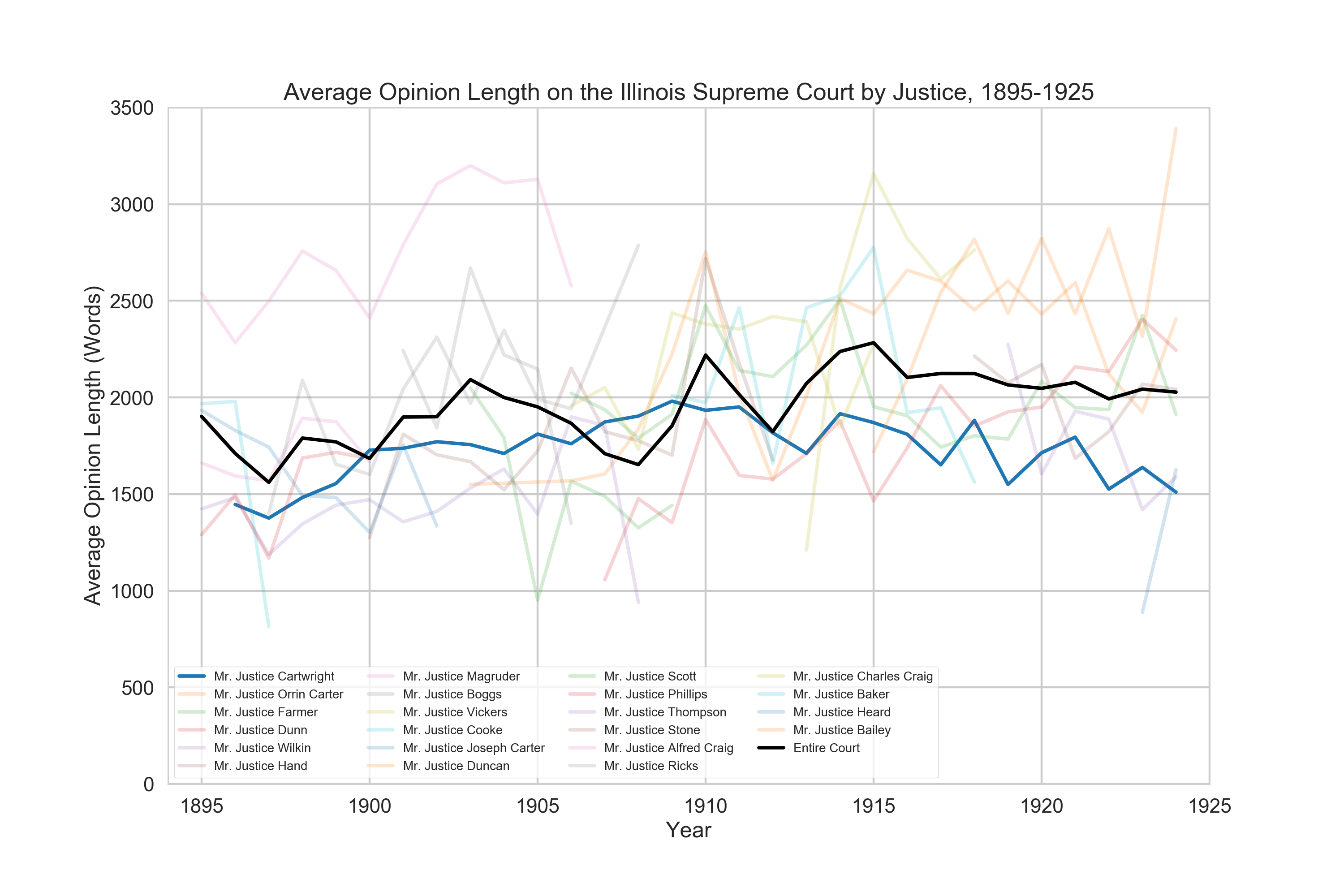

Perhaps a bit of this relative immunity to fatigue can be attributed to the style of Cartwright’s writing. Per the visualization below, Cartwright tended to writer shorter opinions than the majority of his peers – his average opinion totalled about 1,724 words, as compared to the court-wide average of 1,949 words. Justice Orrin Carter, the second most prolific justice on the court in the period examined, averaged about 2,209 words per opinion. Carter’s 1,129 opinions summatively contain 2,493,649 words, whereas Cartwright’s 1,978 opinions contain 3,411,869. Interestingly, Cartwright’s word counts were at their lowest during the beginning and end of his career.

This basic investigation demonstrates just a few of the insights that this dataset offers into the professional life of Cartwright and his peers. In the hands of an interested researcher with questions to ask, a few gigabytes of digitized caselaw can speak volumes to the progress of American legal history and its millions of little stories.

The data used in this blog post can be downloaded on the Caselaw Access Project Website: https://capapi.org/bulk-access/. An iPython Notebook containing all of the analysis and visualization code used in this post can be found on Github here: https://github.com/john-bowers/capexamples/blob/master/CAPDemo.ipynb. Please note that this dataset contains OCR errors and was not cleaned completely – figures are approximate.