The prospect of having the Caselaw Access Project dataset become public for the first time brings with it the obvious (and wholly necessary) ideas for data parsing: our dataset is vast and the metadata structured (read about the process to get to this), but the work of parsing the dataset is far from over. For instance, there’s a lot of work to be done in parsing individual parties in CAP (like names of judges), we don’t yet have a citator, and we still don’t know who wins a case and who loses. And for that matter, we don’t really know what “winning” and “losing” even means (if you are interested in working on any of these problems and more, start here: https://case.law/tools/).

At LIL we’ve also undertaken lighter explorations that highlight opportunities made possible by the data and help teach ways to get started parsing caselaw. To that end, we’ve written caselaw poetry with a limerick generator, discovered the most popular words in California caselaw with wordclouds, and found all instances of the word “witchcraft” for Halloween. We have created an examples repository, for anyone just starting out, too.

This particular project began as a quick look at a very silly question:

What, exactly, is the color of the law?

It turned, surprisingly, into a somewhat deep dive of an introduction into NLP. In this blog post, I’m putting down some thoughts about my decisions, process, and things I learned along the way. Hopefully it will inspire someone looking into the CAP data to ask their own silly (or very serious) questions. This example might also be useful as a small tutorial for getting started on neural-based NLP projects.

Here is the resulting website, with pretty caselaw colors: https://colors.lil.tools/

A note on the dataset

For the purposes of sanity and brevity, we will only be looking at the Illinois dataset in this blog post. It is also the dataset that was used for this project.

If you want to download your own, here are some links: Download cases here, or Extract cases using python

How does one go about deciding on the color of the law?

One way to do it is to find all the mentions of colors in each case.

Since there is a finite number of labelled colors, we could look at each color and simply run a search though the dataset on each word. So let’s say we start by looking at the color “green”. But wait! We’ve immediately run into trouble. It turns out that “Green” is quite a popular last name. Excluding anywhere the “G” is capitalized, we might miss important data, like sentences that start with the color green. Adding to the trouble, the lower cased “orange” is both a color and a fruit. Maybe we could start by looking at the instances of the color words as adjectives?

Enter Natural Language Processing

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is a field of computer science aimed at the understanding and parsing of texts.

While I’ll be introducing NLP concepts here, if you want a more in-depth write-up on NLP as a field, I would recommend Adam Geitgey’s series, Natural Language Processing is Fun!

A brief overview of some NLP concepts used

Tokenization: Tokenizing is the process of divvying up a wall of text into smaller components — typically, those are words (sometimes they are characters). Having word chunks allows us to do all kinds of parsing. This can be as simple as “break on space” but usually also treats punctuation as a token.

Parts of speech tagging: tagging words with their respective parts of speech (noun, adjective, verb, etc). This is usually a built-in method in a lot of NLP tools (like nltk and spacy). The tools use a pretrained model, often one built on top of large datasets that had been tediously, and manually tagged (thanks to all ye hard workers of yesteryear that have made our glossing over this difficult work possible).

Root parsing: grouping of syntactically cogent terms. The token chosen (in this case, we’re only looking at adjectives), and the “parent” of this token (read this documentation to learn more).

Now what?

Unfortunately, we don’t have magical reference to every use of a color in the law, so we’ll need to come up with some heuristics which will get us most of the way there. There are a couple ways we could go about finding the colors:

The easiest route we can take is to just match an adjective in the colors list that we have when we come across it and call it a day. The other, more interesting to me way, is to get the context pertinent to the color, using root parsing, to make sure that we get the right shade. “Baby pink” is very different from “hot pink”, after all.

To get here, we can use the NLP library spacy. The result is a giant list of of word pairings like “red pepper” and “blue leather”. This may read as a food and a type of cloth and not a color. As far as this project is concerned, however, we’re treating these word pairings as specific shades. “Blue sky” might be a different shade than “blue leather”. “Red pepper” might be a different shade than “red rose”.

But exactly what shade is “red pepper” and how would a machine interpret it?

To find out the answer, we turn to recent advances in NLP techniques using Neural Networks.

Recurrent Neural Networks, a too-brief overview

Neural Networks (NNs) are functions that are able to “learn” (more on that in a bit) from a large trove of data. NNs are used for lots of things: from simple classifiers (is it a picture of a dog? Or a cat?) to language translation, and so forth. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are a specific kind of NN: they are able to learn from past iterations by passing the results of a preceding output down the chain, meaning that running them multiple times should produce increasingly more accurate results (with a caveat — if we run too many epochs, or full training cycles — each epoch being a forward and backward pass through all of the data), there’s a danger of “overfitting”, having the RNN essentially memorize the correct answers!.

A contrived example of running an already fully-trained RNN over 2-length sequences of words might look something like this:

Input: "box of rocks", Output: prediction of word "rocks"

Step1: RNN("", "box") -> 0% "rocks"

Step2: RNN("box", "of") -> 0% "rocks"

Step3: RNN("of", "rocks") -> 50% "rocks"

Notice that an RNN works over a fixed sequence length, and would only be able to understand word relationships bounded by this length. An LSTM (Long short term memory) is a special type of RNN that overcomes this by adding a type of “memory” which we won’t get into here.

Crucially, the NN has two major components: forward and backward propagation. Forward propagation is responsible for getting the output of the model (as in, stepping forward in your network by running your model). An additional step is model evaluation, finding out how far from our expectations (our labelled “truth” set) our output is — in other terms, getting the error/loss. This also plays a role in backward propagation.

Backward propagation is responsible for stepping backward through the network, and computing a derivative between the computer error and the weights of the model. This derivative is used by the gradient descent function, an optimization that adjusts the weights to decrease the error by a small amount for each step. This is the “learning” part of NN — by running it over and over, stepping forward, backward, figuring out the derivative, running it through the gradient descent, adjusting the weights to minimize the error, and repeating the cycle, the NN is able to learn from past mistakes and successes, and move towards a more correct output.

For an excellent video series explaining Neural Networks in more depth, check out Season 3 by 3 Blue 1 Brown. Recurrent Neural Networks and LSTM is a nice write-up with more in-depth top-level concepts.

Colorful words

As luck would have it, I happened upon a white paper that solved the exact problem of figuring out the “correct” shade for an entered phrase, and a fantastic implementation of it (albeit one that needed a bit of tuning).

The resulting repo is here: https://github.com/anastasia/namecolor

The basic steps to reproduce are these: We take a large set of color data. https://www.colourlovers.com/api gives us access to about a million labeled, open source, community-submitted colors — everything from “dutch teal” (#1693A5) to a very popular color named “certain frogs” (#C3FF68). We create a truth set. This is important because we need to train the model against something that it treats as correct. For our purposes, we do have a sort of “truth” of colors, a largely agreed-upon set in the form of HTML color codes with their corresponding hex values. There are 148 of those that I’ve found. We convert all hex values to CIE LAB values (these are more conducive to an RNN’s gradient learning as they are easily mappable in 3d space). We tokenize each value on character (“blue” becomes “b”, “l”, “u”, “e”). We call in PyTorch to the rescue us from the rest of the hard stuff, like creating character embeddings And we run our BiLSTM model (a bi-directional Long Short Term Memory model, which is a type of RNN that is able to remember inputs from current and previous iterations)

The results

The results live here: https://colors.lil.tools/ (sorted by date) or https://colors.lil.tools/lum (sorted by luminosity). You can also see the RNN in action by going here https://colors.lil.tools/create

Although this was a pretty whimsical look at a very serious dataset, we do see some stories start to emerge. My favorite of these is a look at the different colors of the word “hat” in caselaw.

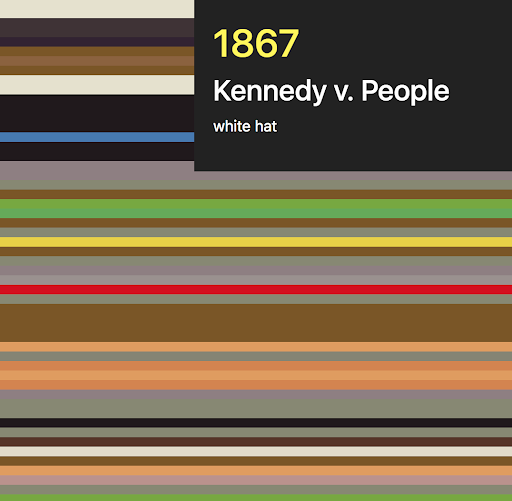

Here are years 1867 to 1935:

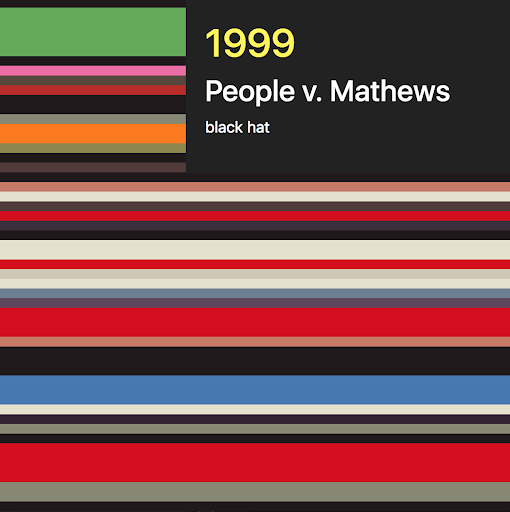

And years 1999 to 2011:

Whereas the colors in the late 1800s are muted, and mostly grays, browns, and tans, the colors in the 21st century are bright blues, reds, oranges, greens. We seem to be getting a small window into U.S.’s industrialization and the fashion of the times (“industrialization” is a latent factor (or a hidden neuron) here :-) Who would have thought we could do that by looking at caselaw?

When I first started working on this project, I had no expectations of what I would find. Looking at the data now, it is clear that some of the most commonly present colors are black, brown, and white, and from what I can tell, the majority of the mentions of those are race related. A deeper dive would require a different person to look at this subject, and there are many other more direct ways of approaching such a serious matter than looking at the colors of caselaw.

If you have any questions, any kooky ideas about caselaw, or any interest in exploring together, please let me know!