The Library Innovation Lab welcomes a range of research assistants and fellows to our team to conduct independently-driven research which intersects in some way to our core work.

The following is a reflection written by Chris Shen, a Research Assistant who collaborated with members of LIL in the spring semester of 2024. Chris is a sophomore at Harvard College studying Statistics and Government.

From poetry to Python, LLMs have the potential to drastically influence human productivity. Could AI also revolutionize legal education and streamline case understanding?

I think so.

A New Frontier

The advent of Large Language Models (LLMs), spearheaded by the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT in late 2022, have prompted universities to adapt in order to responsibly harness their potential. Harvard instituted guidelines, requiring professors to include a “GPT policy” inside their syllabus.

As students, we read a ton. A quick look at the course catalog published by Harvard Law School (HLS) reveals that many classes require readings of up to 200 pages per week. This sometimes prompts students to turn to summarization tools as a way to help quickly digest content and expedite that process.

LLMs show promising summarization capabilities, and are increasingly used in that context.

Yet, while these models have shown general flexibility with handling various inputs, “hallucination” issues continue to arise, in which outputs generate or reference information that doesn’t exist. Researchers also debate the accuracy of LLMs as context windows continue to grow, highlighting potential mishaps in identifying and retaining important information in increasingly long prompts.

When it comes to legal writing, which is often extensive and detail-oriented, how do we go about understanding a legal case? How do we avoid hallucination and accuracy issues? What are the most important aspects to consider?

Most importantly, how can LLMs play a role in simplifying the process for students?

Initial Inspirations

In high school, I had the opportunity to intern at the law firm Hilton Parker LLC, where I drafted declarations, briefs, demand letters, and more. Cases ranged from personal injury, discrimination, wills and affairs, medical complications, and more. I sat in on depositions, met with clients, and saw the law first-hand, something few high schoolers experience.

Yet, no matter the case I got, one thing remained the same –– the ability to write well in a style I had never been exposed to before. But, before one can write, one must first read and understand.

Back when I was an intern, there was no ChatGPT, and I skimmed hundreds of cases by hand.

Therefore, when I found out that the Harvard Library Innovation Lab (LIL) was conducting research into harnessing LLMs to understand and summarize fundamental legal cases, I was deeply intrigued.

During my time at LIL, I have been researching a method to simplify that task, allowing students to streamline their understanding in a new and efficient way. Let’s dive in.

Optimal Outputs

I chose case briefs as the final product over other forms of summarization, like headnotes or legal blurbs, due to the standardized nature of case briefs. Writing case briefs is not explicitly taught to many, if not most law students, yet it is implicitly expected by law professors to keep up with the pace of courses during 1L.

While these briefs typically are not turned in, they are heavily relied upon during class to answer questions, engage in discussion, and offer analytical reflections. Even so, many students no longer write their own briefs, using cookie-cutter resources behind paywalled services like Quimbee, LexisNexis, and West-Law, or even student-run repositories such as TooDope.

This experiment dives into creating succinct original case briefs that contain the most important details of each case, and go beyond the scope of so-called “canned briefs”. But what does it take to write one in the first place?

There are typically 7 dimensions of a standard case brief offered by LexisNexis:

- Facts (name of the case and its parties, what happened factually and procedurally, and the judgment)

- Procedural History (what events within the court system led to the present case)

- Issues (what is in dispute)

- Holding (the applied rule of law)

- Rationale (reasons for the holding)

- Disposition (the current status or final outcome of the case)

- Analysis (influence)

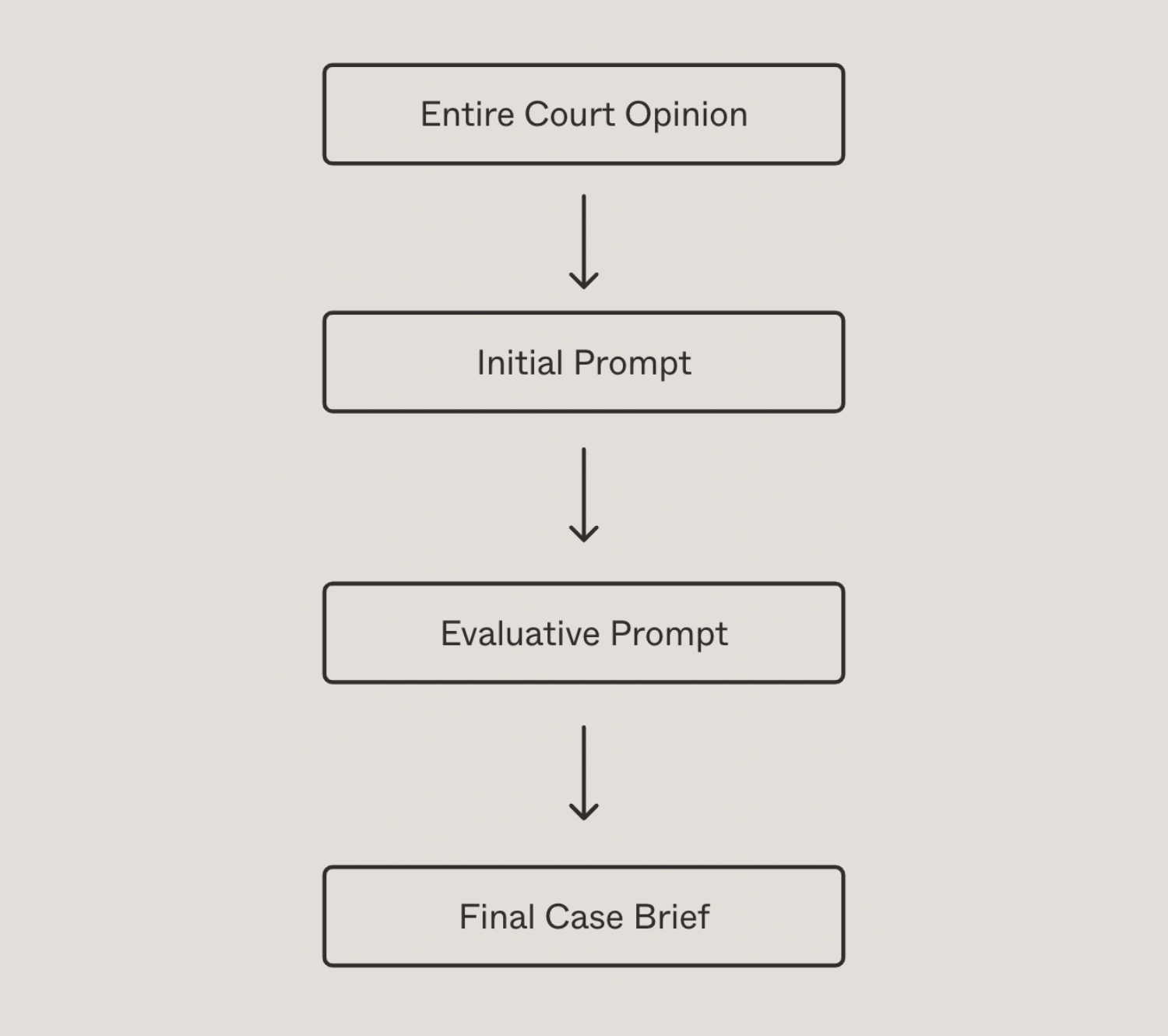

I used Open AI’s GPT-4 Turbo model preview (gpt-4-0125-preview) to experiment with a two-pronged approach to generate case briefs matching the above criteria. The first prompt was designed both as a vehicle for the full transcript of the court opinion to summarize and as a way of giving the model precise instructions on generating a case brief that reflects the 7 dimensions. The second prompt serves as an evaluation prompt, asking the model to evaluate its work and apply corrections as needed. These instructions were based on guidelines from Rutgers Law School and other sources.

When considering legal LLM summarization, another critical element is reproducibility. I don’t want a slight change in prompt vocabulary to alter the resulting output completely. I have observed that, before applying the evaluative prompt, case briefs would be disorganized or often random in the elements the LLM would produce. For example, information related to specific concurring or dissenting judges would be missed, analyses would be shortened, and inconsistent formatting would be prevalent. Sometimes even the most generic “Summarize this case” prompts would produce slightly better briefs!

However, an additional evaluative prompt now standardizes outputs and ensures critical details are captured. Below is a brief illustration of this process along with the prompts used.

See: Initial and Evaluative prompts

Finally, after testing various temperature and max_token levels, I settled on the values 0.1 and 1500, respectively. I discovered that lower temperatures best suit the professional nature of legal writing, and a 1500 maximum output window allowed the LLM to produce all necessary elements of a case brief without including additional “fluff”.

Old vs. New

To test this apparatus, I picked five fundamental constitutional law cases from the SCOTUS that most 1L students are expected to analyze and understand. These include Marbury v. Madison (1803), Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), Brown v. Board of Education (1954), and Miranda v. Arizona (1966).

Results of each case brief are below.

- Marbury v. Madison (1803)

- Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)

- Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

- Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

- Miranda v. Arizona (1966)

Of course, I also tested the model on cases no LLM had ever seen before. This would ensure that our approach could still produce quality briefs past the knowledge cut-off for our model, which was December 2023 in this case. These include Trump v. Anderson (2024) and Lindke v. Freed (2024).

Results of each case brief are below, with attributes –– temperature = 0.1. max_bits = 1500.

Applying a critical eye to the case briefs, I see a successful adherence to structure and how the model has outputted case details consistently. There is also a clearly succinct tone that allows students to grasp core rulings and their significance without getting overrun with excessive details. This is particularly useful for discussion review and exam preparation. Further, I find the contextual knowledge presented, such as in Dred Scott v. Sandford, allow students to understand cases beyond mere fact and holding but also broader implications.

However, I also see limitations in the outputs. For starters, there is a lack of in-depth analysis, particularly for the concurring or dissenting opinions. Information on precedents used is skimmed over and there is a scarcity of substantive arguments presented. In the example of Marbury v. Madison, jurisdictional insights are also left out, which are vital for understanding the procedural and strategic decisions made in the case. Particularly for cases unknown to the model, there is evidence of speculative language that can occur due to incomplete information, prompt ambiguity, or other biases.

So, what’s next?

Moving forward, I’m excited to submit sample case briefs to law students and professors to receive comments and recommendations. Further, I plan to compare our briefs against “canned” ones from resources like Quimbee and gather external feedback on what makes them better or worse, where our advantage lies, and ultimately equip law students in effective and equitable ways.

Based on initial observations, I also see potential for users to interact with the model in more depth. Thought-provoking questions such as “How has this precedent changed over time?”, “What other cases are relevant to this one?”, “Would the resulting decision change in today’s climate?”, and more, will hopefully allow students to dive deeper into cases instead of just scratching the surface.

While I may still be early in the process, I firmly believe a future version of this tool could become a streamlined method of understanding cases, old and new.

I’d like to extend a special thank you for the contributions of Matteo Cargnelutti, Sankalp Bhatnagar, George He, and the rest of the Harvard LIL for their support and continued feedback throughout this journey.