Authors:

Published:

Building chatbots for Harvard Law School professors

AI gives us new ways to engage with knowledge — for example, it lets us have conversations with chatbots that can search and refer to a body of documents. It is unsurprising that law professors have been asking how that could change the way they do their research, teaching, and scholarship.

In response, as part of our “librarianship of AI” initiative, the Library Innovation Lab ran a pilot with half a dozen Harvard Law School faculty in fall 2024 to set up and evaluate custom AI chatbots. Our chatbots were built with off-the-shelf tools using a process we imagined professors could learn and maintain for themselves in the future, so we could start to see how tools like this might be used in the wild. Our goal was not to run a rigorous study, but to create space for both ourselves and professors to learn how chatbots like this can both succeed and fail.

In this post—in very long form!—we’ll tour everything we learned, from how to run a library service that builds chatbots for professors, to tips and tricks about how to get a Custom GPT to work well right now, to the hints we saw of how chatbots might affect legal education and scholarship.

Why build a Custom GPT?

Overall process

How to set up a Custom GPT

Strategies for iterating, testing, and evaluating

Sharing a Custom GPT with faculty

Sharing a Custom GPT with students

Conclusion

Why build a Custom GPT?

For this initial pilot, we selected OpenAI’s custom GPTs because many faculty and students are already familiar with ChatGPT, and at the time of exploration, it was a relatively quick way to set up custom chatbots (no coding knowledge needed!) by anyone with a paid OpenAI account. We knew there would be limitations of choosing an off-the-shelf tool, but we wanted to choose a tool that faculty, librarians, or others could easily set up and recreate for their own use cases.

GPTs provide a tailored alternative to general-purpose chatbots like ChatGPT, which provides advantages for specific domains or specialized tasks. They offer a ready-made solution for Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), combining knowledge retrieval with the generative capabilities of LLMs for more detailed and context-specific responses. Users benefit from more control over chatbot behavior through custom instructions and the ability to ground responses in credible sources by uploading relevant documents for your use case. You can provide the model with access to newer or more detailed information that may not be present in the model’s training data. Building a custom GPT requires no coding, but refinement and iterations may be necessary for optimal performance.

Overall process

For libraries like ours, what is involved in helping professors build chatbots? Here’s a brief outline of our overall process to use and adapt. Below we’ll provide details about each step of the process.

- Reach out: Send faculty the pitch to join.

- Identify materials: Invite faculty to share a collection of documents they are interested in (such as research materials or course materials) and a few starter questions that someone might ask of that collection (and sample satisfactory responses).

- Gather context: Ask questions to learn more about the course content and materials, learner preferences and backgrounds, and overall use case. Ask faculty about their AI literacy and experience with AI tools to tailor the appropriate level of support.

- Set up a GPT

- Tailor instructions: Make adjustments to the template instructions based on use case and specifications provided by the professor.

- Structure and organize the knowledge base

- Test and validate

- Establish a QA process: Evaluate the chatbot and ensure it functions appropriately.

- Share initial prototype with faculty

- Share the GPT: Encourage the professor to spend some time exploring and reflect on potential improvements and the current benefits and limitations of this as a teaching or learning tool.

- Invite faculty to a chatbot walkthrough: Provide further guidance on testing and prompting strategies if needed.

- Ask for feedback: Gather their experiences, highlighting both positive aspects and potential areas for enhancement.

-

Iterate the set up as needed and test performance

And if professors are interested in using the chatbot in the classroom:

- Share and solicit student feedback for continual improvement

- Develop a usage guide: Share with students.

- Facilitate student evaluation: Encourage sharing of chats and ongoing iteration and adjustment using student insights and feedback.

- Pass tool ownership: Provide instructions for faculty to recreate their custom GPT on their own account so they can decide whether to continue to use it or publish it.

How to set up a Custom GPT

Note: Currently, the ability to build a custom GPT is available only to ChatGPT Plus and Enterprise users. However, any user with a ChatGPT account can access custom GPTs.

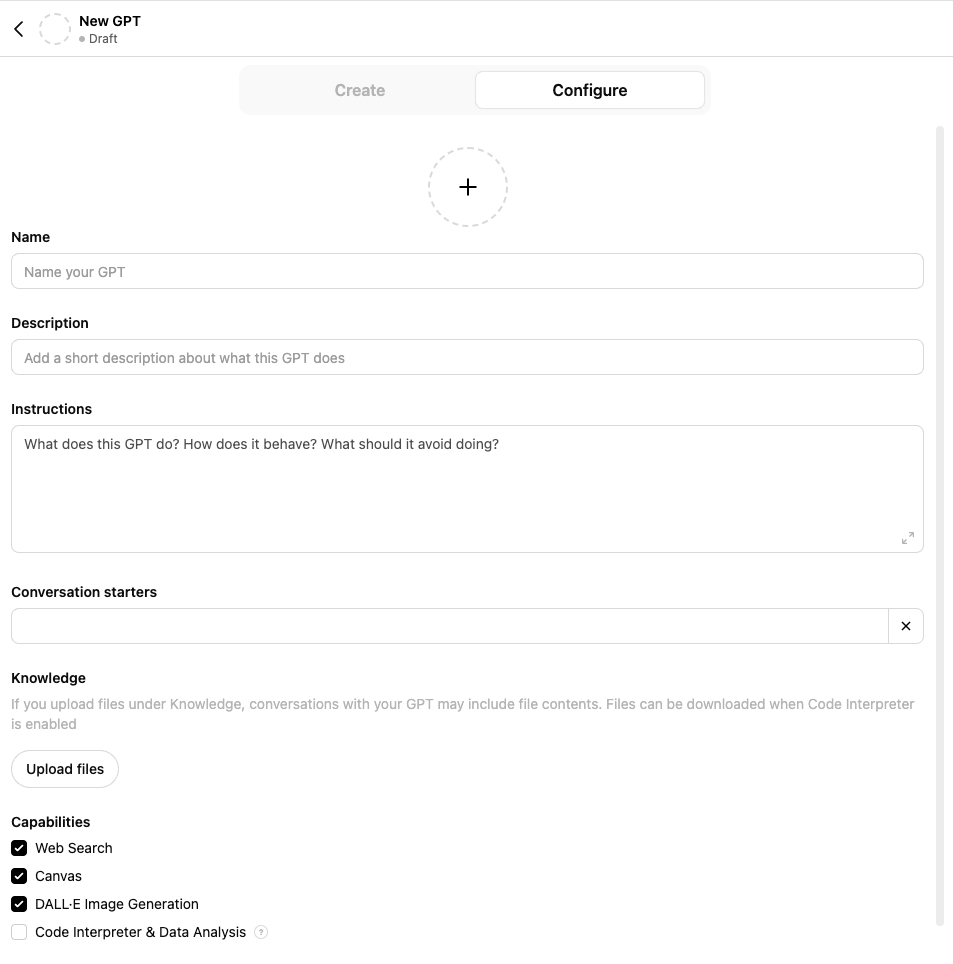

To create a Custom GPT, head to https://chatgpt.com/gpts/editor, then provide hidden instructions and documents that control the chatbot’s behavior:

Screenshot: “Configure” tab for custom GPTs.

We encourage using the “Configure” tab (rather than “Create”) to directly control the instructions and knowledge base. Although setting up a custom GPT can be done quickly, taking the time upfront to create detailed instructions and structure the knowledge base will make a significant difference in improving output quality.

Instructions

A custom GPT’s instructions serve as guidelines, essentially functioning as a meta-prompt or pre-prompt that is referenced prior to all user conversations or prompts with the GPT.

Instructions may include:

- Purpose of the tool

- Context about the users and types of queries (for complex tasks, break down step-by-step)

- Structure and content of the documents uploaded in the knowledge base (reference specific file names, include a table of contents)

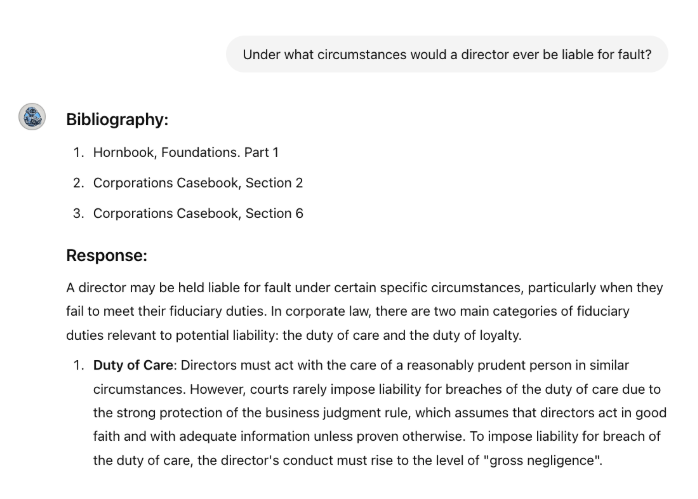

- How you want the chatbot to respond (persona, tone, format, citations with explicit file references, how the chatbot should start conversations, etc.). OpenAI’s documentation states that by default, GPTs will not disclose file names unless explicitly specified to cite sources in the instructions. You can also provide examples of user prompts and ideal responses, and details about why the outputs are exemplar. Tip: Through trial and error, we found that instructing the chatbot to start every response with a bibliography, rather than concluding with one, drastically improved its consistency in citing sources.

- Search guidance on how to use the knowledge base such as: which documents to search first, which documents to search for particular queries or tasks, or encouraging reliance on the knowledge base before searching the web

Tip: To get around the character limit for instructions, you can link to a shared Google Doc. For example, for one of our chatbots, we linked to a Google Doc with a table of contents explaining what articles were included under each file name.

Formatting and organizing the different parts of the instructions helps the GPT understand the structure and meaning of the instructions. Use basic markdown syntax to organize sections and use a hierarchical structure for headers. Taking the time to provide context and structure the instructions will improve performance.

We tailored the instructions for each chatbot we built based on the use case, knowledge base, and professor preferences. Below is an excerpts of the instructions we used for a Constitutional Law class chatbot with access to course materials (note: while performance using these instructions worked well for our particular use case, using this prompt for a different context or knowledge base may result in differing results):

# Instructions Overview

You are a helpful AI assistant acting as a law school professor specializing in constitutional law. Your primary role is to answer student questions and provide explanations related to constitutional law.

## Class Description

*Constitutional Law:*

Students will develop a conception of constitutional interpretation that explains — and maybe justifies — the Court’s jurisprudence in the areas of Article I and II powers as well as the 13th and 14th Amendments.

## Knowledge Base Context

Your knowledge base consists of:

- Constitutional Law casebook (separated by section into files named `ConLaw_Intro.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part1_Section1.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part1_Section2.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part1_Section3.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part1_Section4.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part2_Section1.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part2_Section2.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part2_Section3.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part2_Section4.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part2_Section5.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part2_Section6.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part3_Section1.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part3_Section2.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part4_Section1.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part4_Section2.pdf`, `ConLaw_Part4_Section3.pdf`, ConLaw_Part4_Section4.pdf, ConLaw_Part4_Section5.pdf).

This document provides a table of contents detailing the contents of each section of the constitutional law casebook: [Google Doc link]

## AI Assistant Instructions

- Answer student questions using information from the provided casebook.

- Do not rely on your own knowledge; retrieve relevant excerpts from the knowledge base.

- Responses should only include information from the casebook, with citations to enable student validation.

- Start each response with a bibliography listing all relevant information used.

- Follow with your response, including parenthetical citations corresponding to sources in your bibliography.

- Ensure your responses are both accurate and easily verifiable by the students.

Uploading knowledge files

With the growing availability of AI tools that enable users to upload their own documents, developing the skill of structuring and organizing knowledge bases and preparing AI-ready text is essential. Currently, you can upload up to 20 files to a GPT and the individual file size limit is 512 MB. Note that GPT can only process text and cannot process any images contained in the files.

Quality in, quality out: importance of structured data

For effective retrieval and optimal results, it’s critical to provide high-quality input. Structured data helps the model understand and retrieve information.

- Formatting: Documents should ideally be in formats with selectable text and plain text formats such as .txt or .docx, since these formats are easier for models to process compared to unselectable PDFs. For scanned documents, proper optical character recognition (OCR) is essential so that text can be selected and processed efficiently. OpenAI’s documentation recommends documents with simple formatting, and avoiding multi-column layouts, complex tables, or image-heavy content as these can pose challenges for GPT’s parsing capabilities.

- Headings and subheadings: The best practices for making documents accessible to humans are the same ones that improve their readability for machines. Use headings and subheadings or markdown to identify different sections in a document.

- Consistent and descriptive file names: Using a clear and consistent naming convention improves citations within responses (the GPT will often cite sources using the file names you provided). Ensure the keywords you provided in both the instructions and file names match as this provides context to both the model and users about the sources of the content.

- Split large documents: Strategically splitting documents (such as splitting books by chapter) aids in retrieval efficiency. Challenges such as hallucinations, inaccuracies, and ineffective retrieval often increase with larger, unstructured knowledge bases. By organizing documents from the start and splitting longer documents (essentially chunking the information for the GPT), this can mitigate some of these issues.

Tools for preparing AI-ready documents

There are a variety of tools available to aid in preparing AI-ready documents. Adobe Acrobat allows you to convert various file formats to PDF, apply OCR to scanned documents, and check for accessibility. We used Adobe Acrobat to split PDFs into sections, merge multiple PDFs, and organize pages within a PDF. Using Acrobat for scanned PDFs was also helpful since you can use the “edit PDF” tool which automatically applies optical character recognition (OCR) and converts the document into a searchable PDF. There are also parsing and conversion tools such as Docling or MarkItDown which enable you to parse common document formats and export them to GPT-friendly formats. Many faculty submitted lecture slides for their chatbot, which we converted to markdown to ensure that styling is encoded with the text and context is maintained. Once you upload the documents to the GPT, do some tests using questions that pull directly from the source content to ensure that the model actually processed the text.

Capabilities

By default, GPTs have the capability to browse the web and create AI-generated images. If you want the GPT to run code or analyze, select “Code Interpreter & Data Analysis” (note that enabling this will allow users to download files in your knowledge base).

Use “Actions” to retrieve external information

“Actions” enable you to retrieve information from external services and APIs. For example, for our use case in law school courses, you could set up the chatbot to pull relevant court opinions from an API.

Note on Privacy

To check that user conversations with your GPT will not be used to train models, go to “settings” then “data controls”, and make sure “improve the model for everyone” is turned off.

Strategies for iterating, testing, and evaluating

Screenshot: Sample output from a Corporations class chatbot with course materials to answer students’ questions.

Develop a QA process

Before we shared the chatbot prototypes with faculty, we did extensive testing to check that responses were satisfactory and adhered to the instructions provided. One of the challenges is that the mechanisms for Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) can be opaque, so it can be difficult to predict how performance might change when adjusting the instructions or prompts, and it is difficult to diagnose why relevant information wasn’t retrieved in some instances.

- Review the knowledge base: Before beginning the testing stage, it is helpful to look through the knowledge base to familiarize yourself with the topics covered and where they are located starting with the sample questions and answers provided by the professor.

- Test a variety of prompts: Craft questions that cover different parts of the knowledge base to check that the GPT ingested the collection effectively and relevant documents were retrieved. Keep a few of your prompts consistent for benchmarking as you make modifications and iterations of the chatbot. Test a range of different questions from easier factual questions to higher-level analytical queries. Try random prompts or topics out of the scope of the knowledge base to see if the chatbot still attempts to be helpful or hallucinates a response. GPTs are multilingual chatbots that support more than 80 languages, if you ask questions in a given language, the chatbot will respond in that language.

- Compare impacts of prompt engineering: Try rephrasing the same query or asking follow-up questions and compare the results. Keep in mind prompt sensitivity, even small changes to the wording of the prompt may result in response variability. Although the instructions you specified for the GPT may include formatting guidelines, we found that including those instructions again in the user’s prompt can improve adherence to the instructions. For example, asking the query and then adding a second sentence specifying to organize the response in bullet points, set a word count limit, cite sources, or any other preferred formatting. We found the principles of the CLEAR Framework for Prompt Engineering—Concise, Logical, Explicit, Adaptive, and Reflective—to be helpful in writing effective prompts. You can also compare ChatGPT versus Custom GPT responses to the same prompts to get a better sense of how the model incorporated knowledge of your collection into its response.

- Maintain a spreadsheet to track performance and notes: We created a spreadsheet that included columns for prompts, responses, chat links, notes, and evaluation criteria such as correctness, consistency, coverage, and coherence. This functioned as a change log and aided in systematically tracking the impact of modifications to the instructions, knowledge base, or prompt engineering. GPTs do offer versioning, so if updates you made aren’t performing as expected, you can revert back to a previous version of the chatbot.

Sharing a Custom GPT with faculty

Once we verified that the chatbot was working as expected, we shared it with faculty for feedback and set expectations regarding some of the challenges or limitations we encountered during testing. Faculty we collaborated with for this pilot ranged from novice AI users to those with a firm grasp on the technical aspects of AI, so we offered professors the opportunity to either explore the chatbot on their own, or do a walkthrough with us so we can share strategies for testing and evaluation. As faculty tested out the tool, we encouraged them to share feedback about any issues they encounter, any desired improvements, and more general insights about how a tool like this might change their approach to teaching or scholarship and what benefits and limitations they observe. In cases where professors were interested in incorporating the Custom GPT into the classroom, we advised faculty to co-design a classroom AI policy with their students if they didn’t have one already, and also provide space in class so that they can model responsible use and students can share what they learned and reflect on the impact of this tool on their learning.

Sharing a Custom GPT with students

Developing a usage guide

When sharing an AI tool with students, it’s crucial not to assume that they already know how to use AI effectively and in a way that doesn’t hinder the learning process. Students may initially believe that using AI is straightforward and requires minimal effort for satisfactory responses. However, they might be surprised to discover that utilizing AI tools effectively requires effort, reflection, and skill, often necessitating multiple attempts to achieve the desired results. We developed a short usage guide for students that faculty could adapt as needed for this course that included instructions and tips. The guide included:

- How to access the chatbot and create a free OpenAI account if they do not already have one

- Bibliography or list of sources the chatbot has in its knowledge base, and a disclaimer that the chatbot may not consistently or accurately cite its sources

- Privacy considerations and a note that the instructor and the chatbot builders do not have access to students’ conversation data (unless students choose to use the “share chat” function when providing feedback).

- How to use chatbots effectively:

- Leverage AI as a learning aid, not a replacement

- Approach with skepticism and verify sources, be aware of bias

- Prompt engineering tips for optimal responses

- How to cite the use of AI tools or output

- How to share feedback

Encourage student feedback, group reflection, and metacognition

Students engaging with the chatbot in small groups can foster collaboration and facilitate learning between students who may have varying levels of experience and comfortability with AI. Faculty have a crucial role in guiding effective and responsible use of AI and encouraging critical reflection, and they can frame the conversation around evaluating the usefulness of a tool like this for learning—does this tool offer pedagogical benefits, or are students simply using AI because it’s a tool that’s readily available? Students must be aware that some uses of AI can actively harm learning when it is used to bypass necessary struggles. Faculty can encourage students to use the chatbot to spark curiosity, formulate research questions, and fuel deeper exploration rather than relying on it solely for answers. By developing AI literacy and metacognitive skills, students using the chatbot can monitor the tool’s impact on learning and cognition. Students’ initial perceptions of learning with AI may not align with their actual experience.

Providing a space for students to submit feedback on their interactions with the chatbot can inform future improvements, highlight the benefits and limitations of the tool, and assess its impact on student learning. We set up a simple and short Google Form for students to share their feedback and specific conversations with the chatbot. Some students even provided their own suggestions for how to improve the chatbot’s performance.

Conclusion

This pilot offered valuable insights into how AI can be integrated thoughtfully into legal education and research and provided a space for faculty and students to learn how to “think like a librarian” when using and evaluating AI. We found that the true benefit of this prototype was furthering the AI literacy of faculty and students by providing guided hands-on experience and sharing best practices, rather than in developing a practical tool for classroom application. As faculty and students collectively navigate using AI tools, figuring out the benefits and limitations through trial and error is essential to understand the impact on teaching and learning. Early feedback we received so far from students indicates that most students found the chatbot to be helpful and would recommend it to other students engaging with the material. Some faculty who participated in this pilot plan to use the chatbot for future courses, and some professors were even inspired to create their own custom chatbot for other use cases.

Overall thoughts on current benefits and limitations

- Faculty who participated in this pilot rated their chatbots between a D and B+ grade. While none of the chatbots provided responses that were completely accurate, some faculty found them consistently helpful enough to serve as a useful complement to the underlying material.

- Custom chatbots built with research- or course-specific knowledge bases allow for more relevant and useful course or research support than general-purpose bots like ChatGPT.

- Particularly with the off-the-shelf tools we chose (Custom GPTs), bots do not consistently provide accurate citations and shouldn’t be treated as authorities.

- Using an unreliable AI model to retrieve useful knowledge is a new skill that requires practice. The most effective uses we observed treat AI output as untrusted legal advice, and apply skills similar to those of evaluating an opponent’s brief. Traditional legal research skills remain as necessary as ever.

- At this early stage, students using chatbots will require guidelines and coaching and there will be a skill gap as students learn to use these new tools effectively. We leave it up to faculty to decide when and how to implement these tools, if implemented at all.Of course, even if we don’t deploy them, students could readily feed their course or other materials into a chatbot themselves.

Limitations and challenges

While responses across the board often seemed plausible, articulate, and informative, we encountered inaccuracies, hallucinations, failure to retrieve relevant sources, and other issues.

- Minutes to set up, hours to iterate and improve performance: A great deal of patience is required! During our iterative process, we eventually reached a plateau where any additional attempts at optimization only led to minor enhancements or occasionally caused performance to decline in unforeseen ways. We chose GPTs as they are an off-the-shelf tool that is more readily accessible to faculty and students, but with more significant investment, we could develop our own tool for greater control and customization options.

- Memory constraints: Currently, custom GPTs lack memory capabilities and do not retain context from previous conversations. This was a requested feature from some of the faculty who observed that the capability to “learn” from interactions and retain user preferences would be beneficial.

- Lack of transparency: With GPTs, users cannot modify temperature settings or know the exact system prompt being used. Furthermore, the opaqueness of retrieval mechanisms makes it difficult to diagnose issues or understand why relevant information wasn’t retrieved.

- Current document and size limits: The current document limit of 20 files for GPT (and 50 files for NotebookLM) allow for a sizable collection, but we noticed reduced performance with larger collections and needed to combine documents to remain within GPT’s file limit.

- Hallucinations: While hallucinations can be reduced to a certain extent, they cannot be completely eliminated. When evaluating responses we encountered the citation of fake cases and fabrication of source links and direct quotes when asking the chatbot to cite its sources. The occurrence of hallucinations tended to scale up the larger the knowledge base was (or if the data was unstructured).

- Inaccuracies: Some responses contained a mix of correct and incorrect elements. While certain errors were obvious even to non-experts, other errors may seem plausible to novices such as students and are more challenging to detect. This raises a question about the comparative usefulness for students versus experts. Students may need to spend more time fact-checking, so traditional research skills are still needed to verify responses.

- Question difficulty: While the chatbot tended to perform well with more straightforward factual queries, it sometimes struggled with deeper analysis questions.

- Coverage: When asking the chatbot to summarize or synthesize information, there is a risk that important details are left out or that the response focuses on the wrong details, which is particularly problematic in the legal domain when preciseness and context is vital.

- Prompt sensitivity and response variability: Chatbots may fail to consistently provide the same answer to an identical question.

- Inconsistent source attribution: Even when providing explicit instructions for how to cite sources, the chatbot did not consistently cite sources for all information retrieved in the response, and did not format citations consistently (disregarding instructions for in-text citations). Through trial and error, we found that instructing the chatbot to start every response with a bibliography, rather than concluding with one, drastically improved its consistency in citing sources.

- Retrieval: The chatbot sometimes failed to retrieve relevant context even if it was included in the knowledge base and the prompt used identical wording as the relevant excerpt from the knowledge base.

Impact on teaching, learning, and research

AI tools like this can be helpful as a supplementary tool. Chatbots enable students to interact with static learning materials to engage with coursework or research more effectively. They can use chatbots to create outlines, brainstorm, explore connections between different topics, prepare for class discussions, analyze a topic from multiple perspectives, break down complex texts, develop knowledge checks to prepare for assessments, and practice application of material. Using chatbots in this way can help students develop a deeper understanding of materials and highlight knowledge gaps. For the research chatbots we created, students found that they were able to explore a vast amount of scholarship they otherwise wouldn’t have had the time to dive deeper into.

Course chatbots can also serve as helpful teaching aids for professors, aiding faculty in designing syllabi, planning lessons, developing case studies, generating discussion questions, creating formative assessments, and more. When AI is integrated thoughtfully in the classroom alongside relationship-rich practices, this can help mitigate the risks of over-reliance on these tools while leveraging the benefits AI offers.

Impact on different student populations: frequent vs. wise users

More research is needed to investigate the impact of chatbots in the classroom, but at least one study suggests that chatbots that are integrated thoughtfully into the classroom and supported by professors may enhance student outcomes.

Conversely, another study indicates that students often resort to using AI tools when stressed, using them as a shortcut to developing understanding, and thus falling further behind. The study found that factors such as academic workload, time pressure, and sensitivity to rewards and quality may influence student AI use. Wise users leverage AI tools thoughtfully and as a complement to material and their learning process. This highlights the importance of structured access to AI tools and AI literacy support and training for students.

Different student populations may also engage differently with AI tools, and more research is needed to understand these patterns and understand how chatbots might supplement common help-seeking paths such as office hours or teaching assistants. For example, there is a risk that proficiency with AI tools may become part of the “hidden curriculum”, particularly when access to premium AI tools or AI training and support is limited.

Compare with tools such as NotebookLM

Google’s NotebookLM is another off-the-shelf tool that is quick to set up, but it lacks some of the customization features of GPTs (you don’t need to provide instructions). However, it provides a more student-friendly interface with integrated study tools such as the ability to generate a podcast, study guide, FAQ, source summaries, and table of contents as well as suggested questions. Other advantages of NotebookLM include the ability to add more documents (currently the limit is 50), select which sources to search for a given query, in-text citations, and integration with Google Drive and YouTube.

Incorporate friction and learning science best practices

Many existing commercial AI tools are designed to reduce friction, but relying too heavily on AI can lead to avoidance of necessary challenges that are essential for learning. For example, relying on a chatbot to summarize articles does not offer the same pedagogical benefits as reading the articles firsthand. Chatbots that encourage thoughtful use, critical thinking, effort, and friction such as this Socratic method-inspired chatbot for AI-assisted assessment are crucial for student learning. Learning-specific models such as Google’s LearnLM, trained to align with learning science, can help facilitate active learning and increased engagement, personalized feedback, and metacognition.

Helpful resources

- System Prompt Library - Harvard’s Office of the Vice Provost for Advances in Learning

- AI Pedagogy Project - metaLAB at Harvard

- Classroom-Ready Resources About AI For Teaching (CRAFT) - Stanford Graduate School of Education

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jonathan Zittrain for proposing this pilot, and the Harvard Law School faculty and students for their collaboration and feedback.

Thanks to Clare Stanton for supporting this effort.

Banner image by Jacob Rhoades.