Author:

Published:

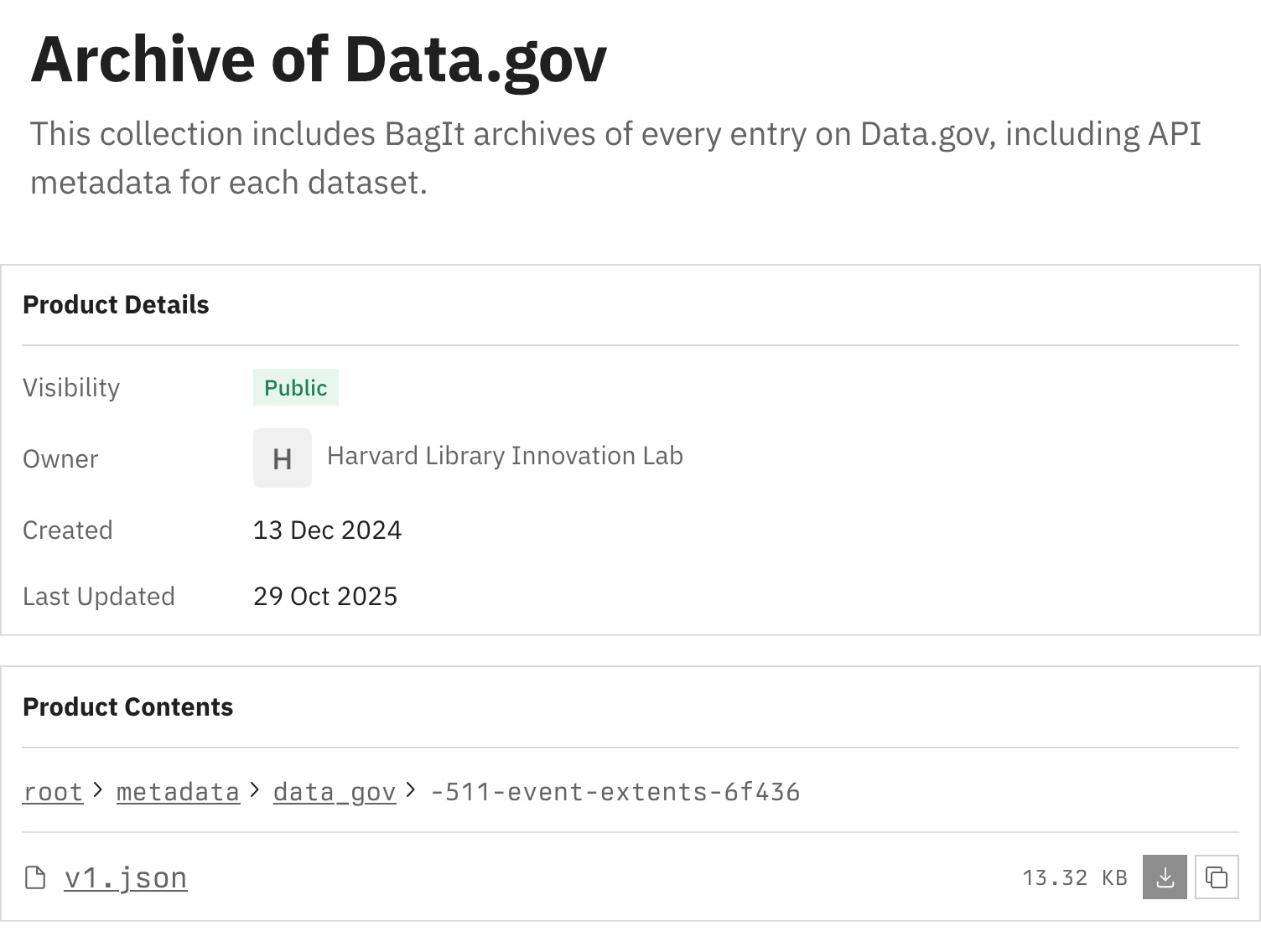

As part of our Public Data Project, LIL recently launched Data.gov Archive Search. In this post, we consider the importance of provenance for large, replicated government datasets. This post is the third in a three-part series; the first introduces Data.gov Archive Search and the second explores its architecture.

In cultural heritage collecting, objects’ histories matter; we care who owned what, where, and when. The chronology of possession of an object through place and time is commonly referred to as “provenance.” Efforts to decolonize the archive have given new life to this age-old collecting concept, as provenance is now often at the forefront of collecting conversations: tracing how and why an object came to be placed (or displaced) in a given museum, library, or collection often is intertwined with histories of colonialism and its accompanying plunder. Projects such as Art Tracks, Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America, and Getty Provenance Index help to record provenance information and to share it across institutions and platforms. Other projects, such as Story Maps of Cultural Racketeering, depict the underbelly of the trade in cultural heritage objects.

Recovery of art stolen by the Nazis, dramatized in films such as The Monuments Men, has brought the concept of “provenance” into the public conversation as well as the courtroom. Many of the legal claims for restitution have been adjudicated based on provenance records.

The provenance of digital collections might seem trivial when compared to such monumental moments. And yet, stories like this have been on my mind as we develop the Public Data Project. How and why could provenance of federal data be needed in the future? When might digital provenance — the marrying of ownership metadata to the digital object itself — matter? Could we imagine it being used to right past wrongs, to return objects to their rightful places, to restore justice?

In the context of government data, provenance most often refers to which government agency or office produced the data. When government data was widely distributed on paper, it was nearly impossible to forge government records — too many legitimate copies existed. In the digital environment, provenance is not so straightforward. Metadata tells us what the source of a given dataset is. But this data is in the public trust, and so its origins are only the beginning of its provenance story. What happens when we start to copy federal data and pass it from hand to hand, so that trusting it means not only trusting the agency that produced it but also those that copied it, stored it, and are serving it up?

As we develop the Public Data Project, we have been considering provenance anew: what provenance data should we record when private institutions, or members of the public, download and preserve public data from their governments? Put another way: if we as non-government actors make government data available to others, how do we maintain trust that this data is authentic, an exact copy of that which was released by the government?

There could be a time in the future when we are just as interested in the changes and inventions of the people who pass government data from hand to hand as we are in the original, unaltered sources. As stewards of federal data, we must then have a responsibility to trace and report data’s ownership histories. This seems, in some ways, even more true because of the very nature of data: it holds mimetic potential. These datasets not only want to be used, but they want to be reproduced. The Enlightenment tradition that vaunts of originality — of an essence that defines an object and that cannot be replicated — seems misplaced here if the dataset remains unchanged from its source version to its replicated versions. In the spirit of scholars such as Marcus Boon who write in praise of “copying,” we might then say that replications of the data are not denigrated at all, just because they are not the original set. And yet, at the same time, we want and need data to retain authority, to know its origin stories. How best to do this?

Those signatures, and the metadata they sign, are one part of publishing robust, resilient archives with irrefutable provenance marks. Through digital signatures that are verifiable using public-key encryption, as well as metadata JSON files that contain details of source and ownership, each dataset has a clear custodial history. Regardless of how users acquire the data, they can check that copies of the “original” datasets — which were first published on a government website, then aggregated to Data.gov, and then replicated by LIL — are unchanged since that point.

When seen through the lens of provenance, characteristics like authenticity, integrity, reliability, and credibility still matter in digital environments. Just as we would seek to authenticate Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man should it turn up at auction after 80 years, so too must we carefully certify our digital cultural heritage.